Mr. Loveless looked at 1,100 schools in California and compared test scores from 1989 and 2009. "Of schools in the bottom quartile in 1989—the state's lowest performers—nearly two-thirds (63.4 percent) scored in the bottom quartile again in 2009," he writes. "The odds of a bottom quartile school's rising to the top quartile were about one in seventy (1.4 percent)." Of schools in the bottom 10% in 1989, only 3.5% reached the state average after 20 years.

Conversely, the best schools tended to remain that way. Sixty-three percent of the top performers in 1989 were still at the top in 2009, while only 2.4% had fallen to the bottom.

His conclusions were that, "School achievement, or lack thereof, is remarkably persistent," and he "the answer may lie in a school's culture—its education DNA."

I tend to be a believer in the group socialization theory of child development, so I'm sensitive to the idea that a school can have a culture that can't be changed by bringing a tougher principal or some more-concerned teachers. However, there's another question that needs to be answered before we start spending money closing bad schools and opening new ones: What if the schools are fine but the kids are failing?

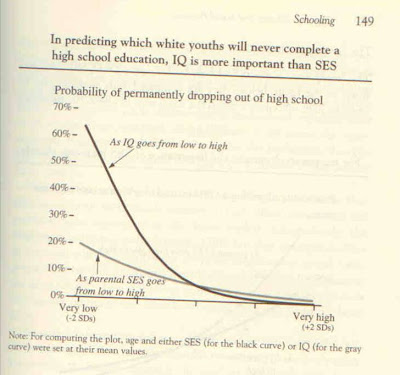

In other words, part of the reason a school's culture doesn't change over a twenty-year period is that the students who attend over that period tend to be similar. I suspect they are particularly similar in terms of wealth and race, both of which are strong predictors of IQ, which is in turn a very strong predictor of school performance. If you think of it in those terms, then the idea that schools would not change much over time is unsurprising.

There can be no doubt that some schools are inherently better than others, but let's please ask some pertinent questions before we charge ahead; we better do a little more research. For example, those few schools that did move from the top to the bottom or vice versa, were there demographic changes in the regions they served? Did the neighborhood gentrify? Did a large company close its doors causing everybody but the poorest and least able to leave?

I'd also like to know whether the kids who leave failed schools after they're closed actually do any better than they did at the failed school. And please, don't talk to me about a some kid who left MLK High School after his freshman year to attend the Topsider Academy and raised his GPA from 0.7 to 2.5. We need to deal with the world as it actually is. These kids won't be plonked into a great environment all of a sudden. They're going to attend another school with DNA that's probably a lot like the one they just left. That's the reality. And I am not sure I see why we would expect this new school to be much different from the old, "failed" one.

A side note:

There's also a bit of a measurement problem here. No matter what we do, there will always be a range of school and student performance. That necessarily means that some schools and students will be worse than the rest. I.e., we cannot all be above average. Perhaps we should ask whether these worst-performing schools are actually good enough. I know that idea isn't popular in the ed biz, but surely there must be some point we'd be satisfied that no school is failing. How do we know we're not there already? I'd love to hear somebody at least address this question in a serious way, including thoughts about benefit/cost. We can always spend another dollar to improve schools, but the return on each additional dollar is diminishing. We're already spending so much; it must be legitimate to ask whether the next dollar we're proposing to spend provides at least a dollar of benefit.