I'm generally a supporter of standards in education. It may seem like that's a trivial statement. After all, who supports education without standards? Yet it turns out to be a major source of division. On one side, we've got those who insist that education has got to mean something if we're going to spend so much on it. The arguments against standards are more varied. Some worry about disparate impact on racial groups. Others worry about politicization of the curriculum. And of course some are teachers who would, understandably, like not be be judged in any way, least of all by the performance of their students. This last group is vocal.

Lately I've gotten to wondering whether the idea of standards is fatally flawed. There are plenty of difficulties with implementing a standards program, most of which can presumably be worked out. But there's one big problem: what happens to the students who can't meet [typo corrected] the standard?

The logic of simply not giving them a diploma is rock-solid. You didn't demonstrate the necessary skill to justify a diploma; therefore, in order to protect the value of the diploma for those who did so demonstrate, we can't give you one. The benefit/cost calculation is impeccable. But the political calculation is not. What are you gonna do with all those students who don't graduate? More specifically, what are you gonna do with all those ninth-graders who realize they will never graduate and simply drop out?

Funneling non-academic types out of high school and into the job market as apprentices, say, is a great idea. It will suit both those students and the ones who remain in high school better. Unfortunately, that's not where we are, and I see nothing in the discussion of standards that addresses this fundamental problem. Instead, the response seems to be that we must help all students rise up to meet the standard. This is not reality and is doomed to failure.

Certainly good teachers and good schools can eke a little more out of bad students. But does anybody really think that just working a little harder is going to do the trick? If you're serious about a standard you must start by acknowledging that some students will never be able to meet it no matter what they do, and that the number who can't meet the standard varies directly with the difficulty of the standard. In other words, the harder the standard, they fewer students will meet it.

Is this controversial? It shouldn't be. We've been dumping resources on education for decades and we've seen little change in the outcomes. It's possible that we just haven't tried the right trick yet, but the more likely explanation is that we're bumping up against some fundamental limits on what can be accomplished. But let's not get hung up on this point. Maybe there's some whiz-bang Ed School theory about how with just the right blend of carrots and sticks you can make a kid with an IQ of 85 into college material. Even if that's possible, do you really think it will happen? In other words, the issue isn't whether most students could meet the standard; it is whether they actually will. That they won't is indisputable. There are too many examples showing us the stubbornness of this fact.

We've seen the beginnings of what happens when academic standards meet political reality in Washington State. Washington's WASL was supposed to ensure that high school graduates meet a high standard in several areas, including reading, math, science, and writing. So far so good. Unfortunately, right from the beginning trouble brewed. In the first sample tests, most students could not pass the math section. What was the response from the political establishment, you ask? Why, they stood up in support of the standards. They braved the outrage of their constituents whose children were in danger of not graduating high school to protect the value of the high school diploma.

No, I'm kidding. They dropped the math section from test and delayed using the remainder as a graduation requirement. What else could they do? In the end, eliminating the WASL was the only plank in the platform of the guy who defeated the incumbent Superintendent of Public Instruction. She lost her job because she proposed and defended meaningful standards. She was right, but her strategy was a Darwinian loser, politically.

We're stuck. You can't have meaningful standards and still give out high school diplomas to pretty much everybody. The solutions to this dilemma seem not to be on the table. Much as it pains me to say so, it seems inevitable that the standards will ultimately lose this battle.

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

Monday, March 8, 2010

Poverty and performance, updated

Diane Ravitch has been a supporter of both school-choice and standards. In a recent article in the Wall Street Journal, she seems to take back her support for both. This is interesting and worthy of discussion of itself, but I thought the most interesting part came in the third-to-last paragraph (emphasis mine).

I know this isn't the main point of her article, but I can't help wondering, does anybody really believe this? I mean, I know we're all supposed to pretend that being poor makes you dull, but isn't the other way around at least as as likely? The irony is that speaking the plain truth, that some kids are not smart enough to meet tough standards, makes her argument against those standards even stronger. Unfortunately, it bumps up against the Immovable Object, the fantasy that we are each born perfect, capable of anything, until our parents and society and I-don't-know-what-all make us flunk out of eighth grade.

Until we're ready to start talking like adults we have absolutely no hope of improving anything.

Update:

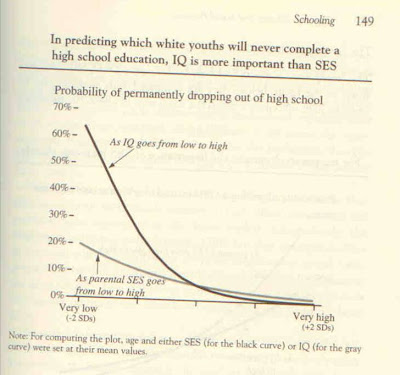

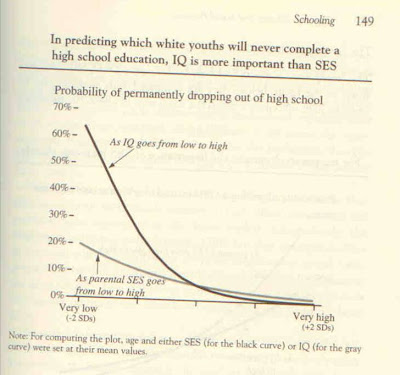

The graph below was scanned (probably illegally - sorry) from Charles Murray's The Bell Curve. It shows the effects of socio-economic status (SES) and IQ on one measure of school performance, namely getting a degree.

The graph clearly shows that IQ is a much better predictor than SES is of at least this particular measure of performance. Look at it this way: if somebody said to you, Tell me whether Joe Blow here ever got his diploma. I'll give you one piece of information about him, you would ask whether he was smart, not whether he was poor. In other words, IQ is a better predictor than poverty.

The current emphasis on accountability has created a punitive atmosphere in the schools. The Obama administration seems to think that schools will improve if we fire teachers and close schools. They do not recognize that schools are often the anchor of their communities, representing values, traditions and ideals that have persevered across decades. They also fail to recognize that the best predictor of low academic performance is poverty—not bad teachers.

I know this isn't the main point of her article, but I can't help wondering, does anybody really believe this? I mean, I know we're all supposed to pretend that being poor makes you dull, but isn't the other way around at least as as likely? The irony is that speaking the plain truth, that some kids are not smart enough to meet tough standards, makes her argument against those standards even stronger. Unfortunately, it bumps up against the Immovable Object, the fantasy that we are each born perfect, capable of anything, until our parents and society and I-don't-know-what-all make us flunk out of eighth grade.

Until we're ready to start talking like adults we have absolutely no hope of improving anything.

Update:

The graph below was scanned (probably illegally - sorry) from Charles Murray's The Bell Curve. It shows the effects of socio-economic status (SES) and IQ on one measure of school performance, namely getting a degree.

The graph clearly shows that IQ is a much better predictor than SES is of at least this particular measure of performance. Look at it this way: if somebody said to you, Tell me whether Joe Blow here ever got his diploma. I'll give you one piece of information about him, you would ask whether he was smart, not whether he was poor. In other words, IQ is a better predictor than poverty.

Monday, February 22, 2010

Tenure: Really?

The stated purpose of tenure is to protect teachers' academic freedom. But is academic freedom really an important issue for public school teachers? Yes, it is. You may remember the story of the high school algebra teacher denied promotion to pre-geometry because of his subversive views on the commutative theorem. Or the middle school PE teacher passed over for chairpersonship of the committee to study installing a roof over the bike rack because he included a two-week course on Ultimate Frisbee, even though the roof was his idea to start with.

Teachers at high school and below are not like professors. They don't do research, they aren't expected to advance their fields. They are supposed to get information from their own heads (and textbooks) into the heads of students. Furthermore, those students are generally minors, which means the true consumers of the services provided by schoolteachers are parents. And when the school in question is a public school, those consumers are taxpayers, as well. So somebody, please, explain to me the benefit to those taxpayers of granting tenure to public schoolteachers.

Protecting academic freedom is not a compelling argument. In fact, the opposite is more true: local parents and taxpayers should control curriculum, not teachers. Let's save the academic freedom talk for college.

The other argument you hear is that tenure protects teachers from arbitrary firing by school boards and principals. Maybe so. But what makes public schoolteachers so special? Those of us in the private sector are subject to arbitrary firing decisions every day. Should we have tenure for accountants? Golf pros? What about tenure for fast-food restaurants? Once you buy a cheeseburger at McDonald's you have to go on buying them there forever.

This is not complicated, people. Tenure is just another example of a special interest group using high-minded language to justify government intervention in a way that benefits that group at the expense of the public.

Down with tenure!

Teachers at high school and below are not like professors. They don't do research, they aren't expected to advance their fields. They are supposed to get information from their own heads (and textbooks) into the heads of students. Furthermore, those students are generally minors, which means the true consumers of the services provided by schoolteachers are parents. And when the school in question is a public school, those consumers are taxpayers, as well. So somebody, please, explain to me the benefit to those taxpayers of granting tenure to public schoolteachers.

Protecting academic freedom is not a compelling argument. In fact, the opposite is more true: local parents and taxpayers should control curriculum, not teachers. Let's save the academic freedom talk for college.

The other argument you hear is that tenure protects teachers from arbitrary firing by school boards and principals. Maybe so. But what makes public schoolteachers so special? Those of us in the private sector are subject to arbitrary firing decisions every day. Should we have tenure for accountants? Golf pros? What about tenure for fast-food restaurants? Once you buy a cheeseburger at McDonald's you have to go on buying them there forever.

This is not complicated, people. Tenure is just another example of a special interest group using high-minded language to justify government intervention in a way that benefits that group at the expense of the public.

Down with tenure!

Monday, January 18, 2010

Two cheers for the AFT!

The head of the second-largest teachers' union, American Federation of Teachers, has agreed to discuss using standardized tests to evaluate teachers. Of course, the devil is in the details. We'll see what the evaluation that comes from this looks like before we declare victory. But this strikes me as a major concession and a significant step in the right direction, where "right" is defined as the direction opposite the interest of the NEA.

The question is Why would the union do this? The teachers' unions have been monolithic in their rejection of virtually any meaningful evaluation of teacher performance. Perhaps it is key that this concession came from the second-largest union. Is this an example of the benefit of competition? In other words, maybe the AFT figured that one way to become the largest teachers' union might be to collaborate with management. Since there is no management in public education, the next best strategy is to collaborate with the standardized testing crowd.

How will this benefit the teachers' union? I don't know, specifically; maybe somebody who knows more about how AFT might expand its membership could comment. It seems clear, however, that being the union favored by the pro-testing crowd, which includes many teachers, by the way, could be an advantage.

The question is Why would the union do this? The teachers' unions have been monolithic in their rejection of virtually any meaningful evaluation of teacher performance. Perhaps it is key that this concession came from the second-largest union. Is this an example of the benefit of competition? In other words, maybe the AFT figured that one way to become the largest teachers' union might be to collaborate with management. Since there is no management in public education, the next best strategy is to collaborate with the standardized testing crowd.

How will this benefit the teachers' union? I don't know, specifically; maybe somebody who knows more about how AFT might expand its membership could comment. It seems clear, however, that being the union favored by the pro-testing crowd, which includes many teachers, by the way, could be an advantage.

Thursday, September 10, 2009

Perspective

Sometimes it's worthwhile to just step back and take an outside view. This chart, from the Cato Institute, offers just such a view with respect to education and spending. As you can see, it shows that over the last 30 to 40 years per-student spending has more than doubled in real terms, while students' performance has been flat.

There must be a million possible objections to this, but the prima facie case is awfully compelling: we're not getting our money's worth when it comes to spending on education.

There's a reasonable argument to be made for emphasizing education and even for funding it publicly. But at what point to we start to ask questions such as Have we reached the point of diminishing returns? Can we plausibly argue that the return on the last dollar of education spending is positive?

As I have pointed out before, while this kind of cost/benefit calculation is done routinely in the real world, where non-performance is punished by bankruptcy or unemployment, it seems never to happen in public education. We are asked to take on faith not only that some spending on education produces worthwhile positive externalities, but that every dollar spent on education produces the same return.

There must be a million possible objections to this, but the prima facie case is awfully compelling: we're not getting our money's worth when it comes to spending on education.

There's a reasonable argument to be made for emphasizing education and even for funding it publicly. But at what point to we start to ask questions such as Have we reached the point of diminishing returns? Can we plausibly argue that the return on the last dollar of education spending is positive?

As I have pointed out before, while this kind of cost/benefit calculation is done routinely in the real world, where non-performance is punished by bankruptcy or unemployment, it seems never to happen in public education. We are asked to take on faith not only that some spending on education produces worthwhile positive externalities, but that every dollar spent on education produces the same return.

Friday, August 7, 2009

Picking your poison

It strikes me that a lot of the arguing that goes on about education boils down to one question: how do you value equity relative to excellence.

I suspect that differences of opinion on questions such as, Do we spend enough on education? Should we have national standards? What is the role of government in education? Are vouchers and charter schools a good idea? are really about the trade-off between equity and excellence.

The fundamental disagreement can be seen this way. The graph below shows two hypothetical distributions of educational "goodness." Both options are represented by Gaussian curves, but they could be any shape. Option 1, the "Unfair but excellent" distribution, has a higher average, but more extremes at the high and low ends. Option 2, "Fair but mediocre," has a lower average but a tighter range.

If you could wave your magic wand and select either distribution for education in America, which would you choose?

If you could wave your magic wand and select either distribution for education in America, which would you choose?

There's no wrong answer, here. There's an argument to be made for either being better. The one you'll choose depends on whether you think equity or excellence is more important. I suspect that much of the educational establishment (can I use that term?) places more weight on equity -- ensuring that no child is left behind. Somebody like Charles Murray, who believes educating the future elite is critical, would disagree.

So? What would you do?

I suspect that differences of opinion on questions such as, Do we spend enough on education? Should we have national standards? What is the role of government in education? Are vouchers and charter schools a good idea? are really about the trade-off between equity and excellence.

The fundamental disagreement can be seen this way. The graph below shows two hypothetical distributions of educational "goodness." Both options are represented by Gaussian curves, but they could be any shape. Option 1, the "Unfair but excellent" distribution, has a higher average, but more extremes at the high and low ends. Option 2, "Fair but mediocre," has a lower average but a tighter range.

If you could wave your magic wand and select either distribution for education in America, which would you choose?

If you could wave your magic wand and select either distribution for education in America, which would you choose?There's no wrong answer, here. There's an argument to be made for either being better. The one you'll choose depends on whether you think equity or excellence is more important. I suspect that much of the educational establishment (can I use that term?) places more weight on equity -- ensuring that no child is left behind. Somebody like Charles Murray, who believes educating the future elite is critical, would disagree.

So? What would you do?

Friday, July 3, 2009

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)